The 18-year old gunman Salvador Ramos who fatally shot 19 children at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, claimed to be a victim of bullying. In the fourth grade, classmates teased him over his stutter, clothing, and haircut. But Ramos is not unique. According to a study by the University of Washington and Indiana University, 97% of bullies were also victims.

Preventing aggression in schools became the focus of BraveUp, a solution created by recent university graduates. The platform is now available in schools in Texas, Idaho, Alabama, Georgia, Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts.

How it all started

Originally from Chile, the startup’s founder, Alvaro Carrasco, identified the need for this service by accident. His first business, an online platform allowing students to assign ratings to classes, came to the attention of a bullying victim, a Colombian girl in Chile who was teased for being an immigrant and had nowhere else to go.

Since then, Brave Up has been focusing on preventing bullying at schools. The platform was first launched in LatAm. The solution is now available in Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, Honduras, Salvador, and Costa Rica.

After entering the American market, founders realized it’s a different ballgame. In the U.S. children study and socialize in frequently changing environments, such as elementary, middle and high schools. In most LatAm countries, kids are often in one group for many years, and so they know their peers very well. Thus, extreme violence is rare.

“The cases in the U.S. tend to be more aggressive and violent,” said Juan Ramirez, the partner at BraveUp responsible for the U.S. expansion. “Also, schools are more focused on getting students into universities rather than bullying. By using BraveUp, they can avoid some extreme situations, such as fights.“

How anti-bullying works

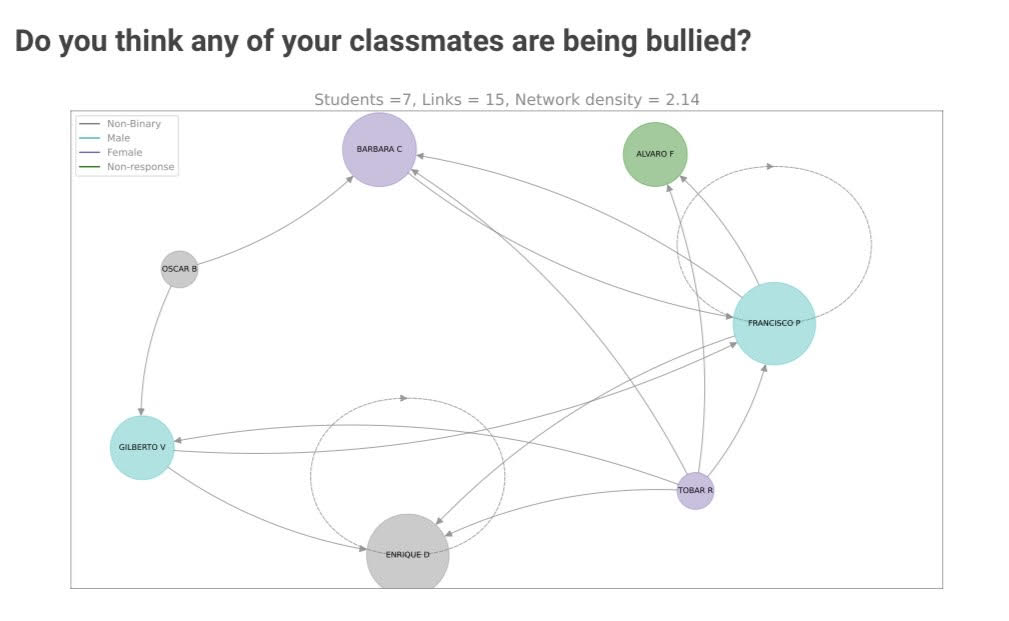

BraveUp provides communication channels where students can connect with the school counselors, either anonymously or under their names. A data-based relationship map allows to identify “bridges” or mediators, someone who has friends and can connect outsiders with the “popular guys”.

The information is collected through a simple 7-question online survey that takes 5-15 minutes. Based on the results, BraveUp optimization and predictive algorithms generate data visualization maps that can quickly identify and flag risky situations, social relationships, and bullies.

“We provide visual graphics on why the victim and other students believe someone is bullied,” Ramirez said.

The solution is normally acquired by school districts. Sometimes NGOs, associations, or companies sponsor BraveUp so that schools with smaller budgets can access the technology. The startup raised around $1 million from Go Ahead VC and Starta VC funds.

The platform is following FERPA (The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act), a federal law that affords parents the right to have access to their children’s education records and SOPIPA (Student Online Personal Information Protection Act).

Is technology better than parents?

Children returning to schools after online learning trust technology more than humans. “It’s an emerging trend,” Ramirez said. “It’s easier for them to report a problem to an app rather than talk to teachers or parents.”

Cyberbullying is also gaining popularity. When classes are finished and teachers think kids are no longer their problem, children are interacting — in games such as AmongUS. “BraveUp can show what’s happening outside the classroom,” Ramirez said.

Ramirez believes BraveUp can empower teachers through technology and data. “Sometimes it’s obvious what’s going on, but the situation isn’t named,” he said. “Technology brings bullying into the spotlight, helping people to see the problem.”

The pandemic changed the way children socialize. “They don’t know how to put their negative emotions in words, and so just hit it up more often”, Ramirez said.

Eventually, the platform’s founders want to create a “bullying rating” — something like a credit score for schools. “The data will be only available to counselors and teachers so they know where they stand,” Ramirez said. “There are plenty of schools who say they have no bullying, but it’s only because they’re not measuring.”