Tomas Uribe’s first experience as an entrepreneur was with his own band in Colombia. He treated his music enterprise as a business, hiring designers and managers, and selling to brands. At some point, he built his own pedalboard — a flight case that serves as a container, patch bay, and power supply for an electric guitar’s effects pedals. Later Uribe launched a manufacturing business to build pedalboards and flight cases for the live entertainment industry.

His band traveled and performed enough for Uribe to realize that New York’s vibrant music scene and mix of cultures made it his dream city. He moved here to pursue a degree in media and technology at Parsons School of Design, and later worked for a tech startup before launching his own business, Stereotheque.

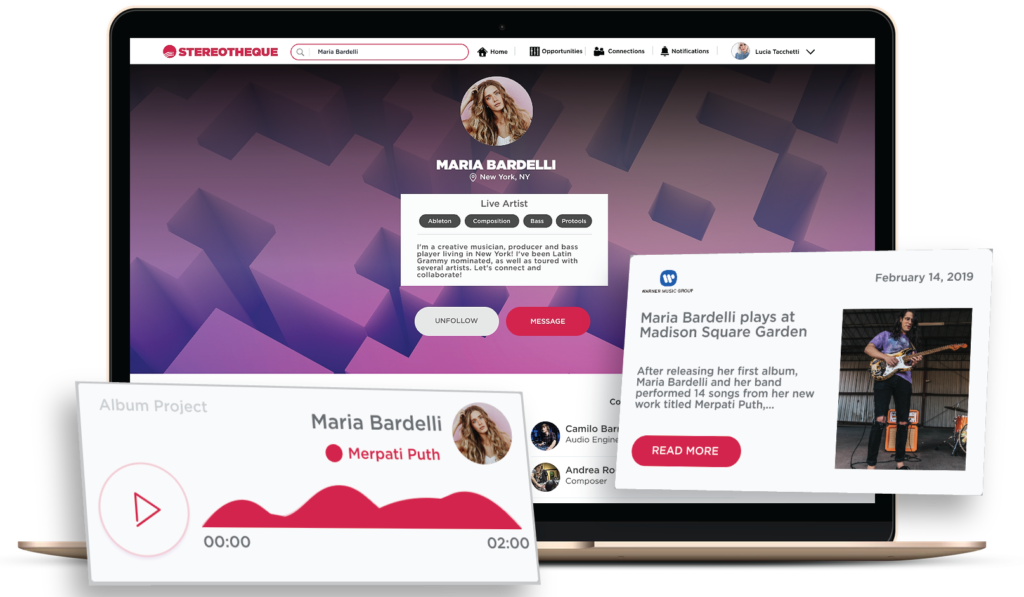

“I had been trying to understand how to find more creative gigs,” he said. “It’s difficult in New York, so I started thinking of how artists can create their own opportunities.” That’s how Uribe got the idea for a network where anybody could showcase their projects, collaborate, and meet clients. “Stereotheque highlights the work people do instead of focusing only on the years of experience they might have,” he said.

Investment for a music startup

For a musician, launching a tech startup was all about the learning experience. “As a creative person, I tend to generate a lot of ideas rather than focus on just one. This had to change,” Uribe said.

Another challenge was finding capital to launch the project. Stereotheque was strapped for cash. The startup managed to receive a number of small grants and investments from the MIT Technology Review, the NYU Entrepreneurial Institute, the New York-based Starta accelerator, as well as angel investors in Colombia and around the world.

“It’s certainly been more difficult for me as an international founder: when we just started, I didn’t have access to business loans, didn’t have a credit history or guarantors to vouch for me. Investors often have more support for people coming from a certain pedigree, a traditional background. This means less risk for them, so they are looking for the signs, like a Stanford MBA.”

Arts during the pandemic

COVID-19 has hit all performing industries around the globe, with many artists, actors, and musicians out of work. “We now have 6,400 users. During the period of lockdown and isolation, the number of creatives using our platform has increased by 25 percent,” Uribe said.

“People can’t go to bars to perform, and any events involving personal interactions have been canceled, so we decided to build a tool that could help our users. In just three days, we launched Covid Aid, a lightweight app for musicians and artists to look for available financial resources during the pandemic.”

According to Uribe, artists from different countries are currently using the service, especially in Latin America, where creatives and freelancers don’t have enough resources and support from the government.

“The biggest challenge for creatives is to convert their skills into a paid opportunity.” Uribe believes that artists in the post-pandemic world will have to learn how to collaborate and work remotely.

How to succeed in the U.S. as an artist

“You have to be agile with your skills and abilities and learn how they can fit into other ecosystems,” Uribe said. “You can be a very good bass player, but you might not fit with the band.”

“In the U.S. and especially in New York, the music industry is a lot about who you know, and the only way to meet people is by being very proactive. You can’t just stay in your studio and expect to be discovered.”